Heritage in the Drum with Hrag Kalebjian of Henry’s House of Coffee

The story begins with Hrag’s grandfather in Lebanon. Coffee wasn’t a product on a shelf; it was part of hospitality. You couldn’t buy roasted coffee in a big box store—because there were no big box stores. Beans arrived from Colombia, Brazil, and other origins, and families roasted them at home.

You can watch the video of our interview at the bottom of this article.

The roasting was primitive by modern standards:

- Coffee in a pan or wok over an open flame

- Later, a small hand-turned tumbling drum

- A song instead of a timer or data logger

Hrag’s father grew up in that environment. As a teenager, he roasted coffee for the bakery’s customers. The war in the 1970s eventually pushed the family to emigrate. They landed in the United States with a background in roasting and a willingness to start over.

In San Francisco’s Armenian community, Hrag’s father met “Uncle Andy,” who owned a small European goods store called House of Coffee—a place that sold jams, crackers, cheeses, candies… and roasted coffee.

In 1983, he bought the business.

At first, he kept it as a European specialty store. But as brands like Starbucks and Peet’s popularized coffee in the Bay Area, he saw where the future was heading. In the early 1990s, he remodeled the shop, dropped the imported goods, and went all-in on coffee—buying a larger roasting machine from a then-small company called The San Franciscan Roaster Company.

While all this was happening, a young Hrag was mostly annoyed.

Weekends meant being dragged to the shop instead of watching He-Man and Scooby-Doo. His job was packing coffee in the back room where it was cold and quiet. His father pushed him toward education: “You have to go to college. I want you to be somebody.”

So he went to UC Davis, majored in economics, and spent about ten years in corporate finance.

But coffee—and the family business—never went away. It just waited.

The Corporate Review That Changed Everything

Before he came back to Henry’s, Hrag had what many people would call a great job. At AAA in California, he led an insights and analytics team, translating numbers into stories for the executive team. He reported directly to the CEO. It was intellectually challenging, he was good at it, and on paper it made sense.

Then came a performance review.

For years, he’d received fives on a one-to-five scale. But a new manager, who barely knew his work, gave him a three. It didn’t affect his salary or bonus—but it cut into something more important: his sense that the system was fair.

It felt like pure office politics. The kind that can drain your energy in a way no late-night project ever could.

At the same time, his father had begun quietly asking hard questions about the future of Henry’s. He was older, still working tirelessly, still loving the roastery—but wondering what came next. Sell to an employee? Find an outside buyer? What happens to a legacy when the person at the center of it eventually steps back?

Hrag, a man of faith, prayed about it. The answer wasn’t thunder and lightning. It was gradual clarity: a growing emptiness for corporate life and a growing conviction that the family business deserved a shot.

“What’s the worst that could happen?” he asked himself.

He could go work there for a few years. If it didn’t work, he could always return to the corporate world.

On July 1, 2013, he stepped away from the corporate path and stepped into Henry’s House of Coffee full-time.

When Your Neighborhood Changes, So Must You

One of the most powerful threads in this episode is how place shapes a roastery.

When Hrag’s father bought the business in 1983, the neighborhood was largely European—hence the European goods. Over time, those customers retired, moved, or passed away. The buildings changed hands. New families moved in, many of them Chinese and Taiwanese.

Business dropped.

His father noticed people walking by, looking in, and continuing on without coming inside. He knew the coffee was good. The question wasn’t quality; it was connection.

So he did something simple and deeply smart: he hired someone who spoke Mandarin and Cantonese.

That person stood outside for an hour at a time, offering samples and inviting people in—in their own language—with one small catch: “If you want milk and sugar, you have to come inside.”

The tactic worked. Word spread through the tight-knit community. Over the next few years, Henry’s turned into a beloved stop for the neighborhood’s East Asian residents, many of whom still come today.

Fast forward to when Hrag joined full-time. He started noticing another shift.

Out the front window, he saw young people in athleisure walking their dogs. The Sunset was becoming “the last affordable place” for a new generation. The shop, last remodeled in the early 1990s, risked looking less like a classic café and more like a relic.

He didn’t want Henry’s to feel outdated. He wanted it to feel timeless.

So he did the simplest and hardest thing: he asked customers what they wanted.

Their answers were straightforward:

• More seating

• More breakfast items

• More coffee options

In 2017, they remodeled: new layout, more seating, an updated menu, and a refreshed design that could welcome both longtime regulars and newly arrived neighbors.

The heart stayed the same. The environment evolved.

If you’re running a small roastery or café, the lesson is sharp and encouraging:

You don’t have to change who you are. But you do have to listen to who’s walking past your door.

Dark Roasts, Specialty Coffee… and Picking a Side

When he first jumped into the coffee industry, Hrag did what many new roasters do: he went to a roasting course.

For two weeks in Marin, he studied modern specialty coffee: lighter roasts, high-acidity origins, meticulous development curves, and a strong emphasis on honoring the farmer by preserving delicate flavor notes.

Then he went home and realized something:

“Everything they’re teaching me is the exact opposite of what my dad is teaching.”

His father’s style is dark.

Blends over a long list of single origins.

Comfort and smoothness over bright, sparkling acidity.

In many corners of the specialty world, that’s treated as a mistake—“burning the coffee.” But Hrag had something theory doesn’t: decades of customer feedback.

People told him, over and over:

- “I don’t have to put milk or sugar in this.”

- “It’s so smooth.”

- “I never drink black coffee, but I can drink this black.”

He faced a choice. Chase the lighter-roast trend or lean into what his family and community already loved.

Being in the coffee industry because of heritage—not hype—gave him clarity. He chose to honor what his father and grandfather built.

Today, Henry’s niche is proudly clear:

Classic, quality, dark roasts that are incredibly smooth.

Coffee that tastes like coffee, rooted in Armenian tradition, roasted for the Sunset District and beyond.

As Bill puts it in the episode: “If you’re meeting the community and cultural needs of where you’re at, you’re doing it right.”

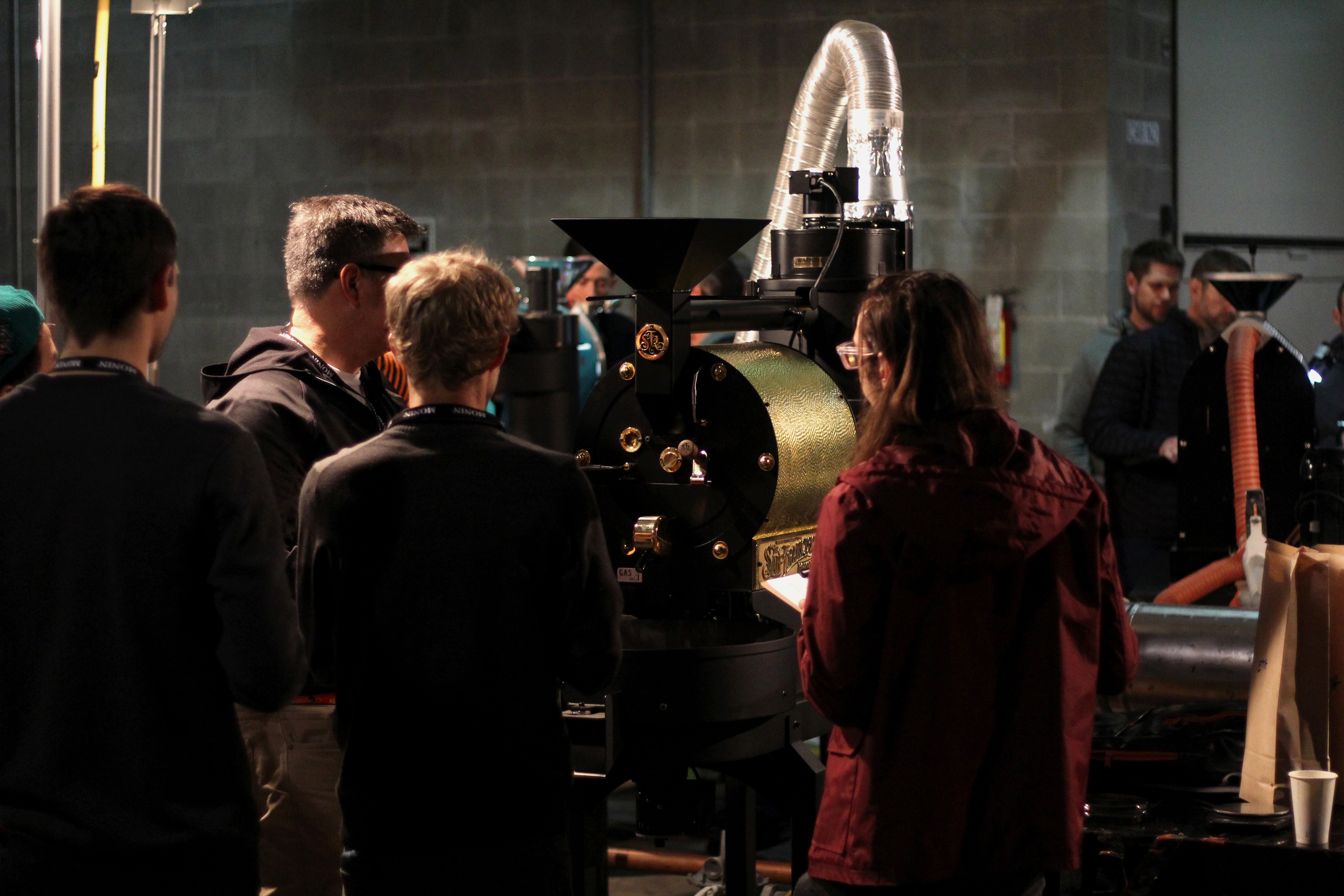

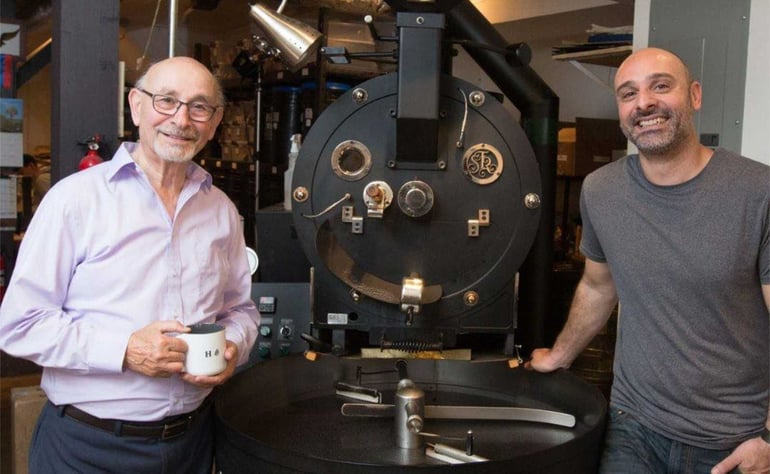

The Roaster Behind the Story

Behind the scenes at Henry’s, one constant has been the machine doing the work.

For about 40 years, Henry’s has roasted on San Franciscan roasters—only two machines in that entire time.

Why stay that loyal?

For Hrag, it comes down to a few core things:

- Simplicity – Easy to operate, intuitive for a working roastery.

- Durability – Built like a tank; a true workhorse.

- Serviceability – When something needs attention, parts can often be sourced locally.

- Fit – From small-batch to “beast” sizes, there’s a San Franciscan that fits each stage of growth.

When aspiring roasters ask him what equipment to buy, his answer doesn’t waver:

“This is the roaster I use. I’ve used them for 40 years. I don’t have any desire to go anywhere else. It just works.”

In a business built on legacy, that kind of reliability isn’t a line on a spec sheet. It’s part of the story.

Advice from a Third-Generation Roaster

Toward the end of the conversation, Bill asks Hrag what he would tell someone who’s just thinking about making the leap into coffee.

Here are his big takeaways:

Figure out your niche and story before you sign a lease.

Buying gear and designing spaces is the fun part. The hard work happens at a desk, asking:

• “What’s my 15-second elevator pitch?”

• “What’s different about us?”

Until you can answer that, you’re not ready.

Understand that coffee is harder than it looks.

Especially in expensive cities, coffee shops are tough. Rent, staffing, equipment, and inventory costs add up fast. Passion is required, but so is grit.

Choose tools and partners you can trust long-term. A roaster that simply works, year after year. Suppliers who pick up the phone. Community connections that last decades. Those matter more than chasing trends.

For Hrag, the “performance review” now happens at the register, not in a conference room. When customers keep coming back and bringing friends, that’s the five out of five.

Useful Links

- Henry's House of Coffee webpage is here: https://henryshouseofcoffee.com/

- Hrag roasts on the San Franciscan SF-25

Watch the full interview